Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Introduction

- The Crew of Linus J. Box

- „A typical bombing mission….“

- The attack on Misburg on 11/26/1944

Introduction

WELCOME TO MY ABBREVIATED PART ABOUT THE „ARK ANGEL“.

The „Ark Angel“ was an American bomber, type B-24 J, serial # 44-40073.

This four-engined aircraft belonged to the American 8th Air Force and crashed on November 26, 1944.

On my home page concerning Oerie I dedicated a chapter to this crash.

On this Thanksgiving Day 1944 all nine crew members including Pilot David Bennett lost their lives.

The „Ark Angel“ was an American bomber, type B-24 J, serial # 44-40073.

This four-engined aircraft belonged to the American 8th Air Force and crashed on November 26, 1944.

On my home page concerning Oerie I dedicated a chapter to this crash.

On this Thanksgiving Day 1944 all nine crew members including Pilot David Bennett lost their lives. The pages on www.oerie.de deal with the circumstances of the crash, the search for family and friends of the crew members and thesearch for information about this crash.

On the pages of thomas-pohl.com I emphasize the military/historical pages a bit more.

Before „Ark Angel“ with the crew of David Bennett crashed on 26.11.1944 she operated under the crew of Linus J. Box. Before box and his crew handed the plane over to Bennett they flew quite a few missions without any damage.

Shortly after the transfer the plane crashed on this eventful Thanksgiving Day.

I would like here to tell a bit more about the Box crew, the B-24 and the air battle over our area on November 26, 1944.

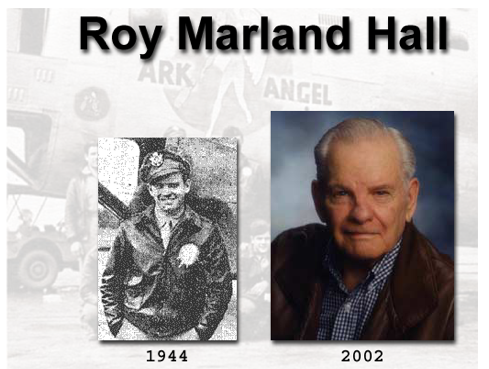

I use this occasion the thank once more all the people who have assisted me in my research, in particular John Meurs and Roy Hall.

However, before I continue telling about „Ark Angel“ on the following pages, I would like to say something that’s important to me:

During WW II 60 million people lost their lives world wide. That’s more or less the population of Germany before the reunion.

Sixty million destinies and most of them are forgotten.

For instance, on November 26, 1944 the nine crew members of „Ark Angel“ lost their lives. So did many people during the attack on Misburg.

We don’t appreciate the dead when we now would start to compare them: whether they were civilians or soldiers. They still remain dead.

We cannot weigh one against another and you cannot really win a war: the „victor“ only seem to have lost less.

If war has a „sense“ then only when we continue remembering the sorrow it brings and when we make efforts to avoid future wars.

I published this story in 2007

The Crew of Linus J. Box

In November 1944 the „Ark Angel“ crashed near Oerie. All of the crew members died.

But there was another crew than flew their missions rather succesfull with the B-24J.

From left to right (standing): O. J. A. Brien (Gunner), L. J. Box (Pilot) George C. Shiaras (Co-pilot), Holland J. Stephens (navigator), Roy M. Hall (Bombardier), John T. Keene (chief ground crew), unknown mechanic.

From left to right (kneeling) : Louis J. Szaflarski (gunner), Edras T. James (gunner), Donald Hassen (flight engineer & gunner), Henry L. Delsignore (radio), Harold L. McLellan (gunner), unknown mechanic.

Picture taken after 19th mission.

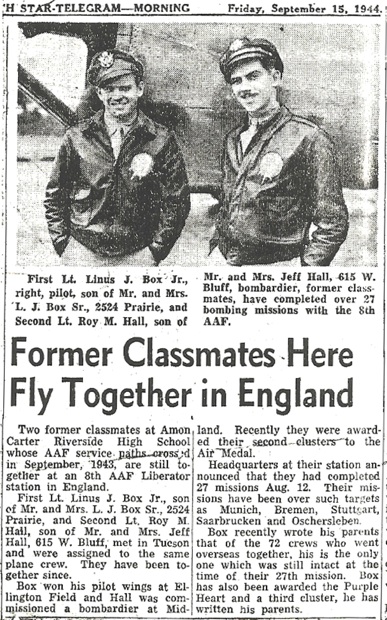

Roy Hall and Linus J. Box not only serve in the same aircraft, but also shared the same school bank:

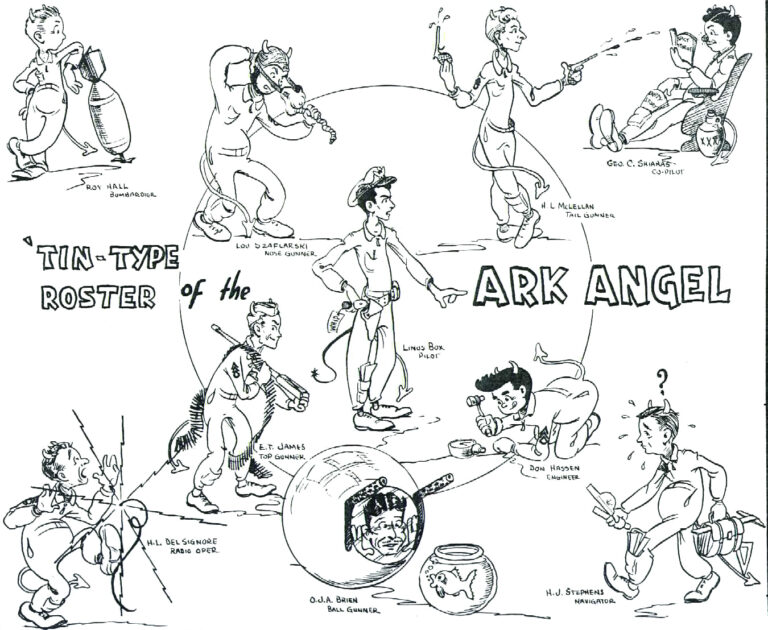

Linus J. Box was a gifted artist. He immortalised his crew in the following caricatures:

The ground crew of the „Ark Angel“:

The picture above shows three ground mechanics of „Ark Angel“. John T. Keen is the man in the middle. They made sure that that after each mission the aircraft was airworthy again. The right hand picture shows John T. Keene 50 years later. He was one of the initiators of the search for the graves of the Bennett crew. (see also „The last flight of the ‚Ark Angel‘ “ at www.oerie.de )

John T. Keene died in 1993. We certainly would have come together much earlier if internet in its present form would would have been available ten years ago.

After he had learned that the people of Oerie had buried the dead of the crash of November 1944, Mr,. Keene thanked the inhabitants of Oerie:

„…we were not enemy of German people, only leader and form of government we were not for. As for your people we have always respected and thought well of before and after the conflict. I want to thank you and your people who were so kind and humane to give these men a Christian burial, minister and coffin ….“

Oerie in 2007

„A typical bombing mission….“

„When all our bombs fell together over a city, I remember looking down and wondering what the poor citizens were thinking with all those bombs exploding around them.

We could never hear the explosions themselves; we could see them and each of us had his own thoughts about the numerous tragedies happening on the ground but we never talked about it.

It was just a distasteful job….“

In the mornings when we were scheduled for a mission, we were awakened several hours before takeoff by an orderly, and sent to breakfast.

Breakfast was always an ordeal for me, as well as for most of us. Powdered eggs were all the eggs we had, but if we were scheduled for a particularly difficult mission, someone scrounged around and found fresh eggs for

breakfast. Likely as not, the idiots who were chosen to be cooks would fry up all the eggs in advance and by the time we got to them they were congealed in cold grease.

After breakfast we would hurry to the briefing room to see what was in store for us this day.

As we filed into the room, we would see a large wall-map covered by a curtain. Behind this curtain was our mission, and the return trip, outlined by pins and a string. When we were all seated, someone drew the curtain and we saw for the first time where we were bombing that day.

If the string led deep into Germany, there was a loud groan throughout the room for we knew we were in for trouble.

The route was supposed to be planned to avoid the areas where the anti-aircraft fire was known to be heavy, but occasionally a mistake was made which the bombing crews paid for.

The briefing officer then would give a general briefing concerning the trip and the weather officer would tell us what to expect from the weather. Then the meeting would breakup into separate Pilot briefings, Navigator briefings and Bombardier briefings. In the Bombardier briefings, we were given the exact aiming point and made to familiarize ourselves with the general area.

A medical officer was always present and would give us Benzedrine tablets to wake us up and keep us alert if we wanted them.

After these briefings, we would all be loaded into Jeeps or trucks and carted out to our aircraft. The maintenance and loading crews would have worked most of the night and the bombs would already be loaded.

Our aircraft could carry four 2000-pound bombs. They could be manually released or automatically released by the bombsight.

After takeoff, we would circle over the field until the last plane of our group took off, then form into formation and head for the coast. Enroute, we would check our guns and maybe fire a few rounds to be certain they were in working order. Each of our aircraft had ten .50 caliber machine guns firing, as I recall, 500 rounds per gun.

As we hit the French coast, every man went on the alert. Our route to the target was carefully planned to

avoid any known anti-aircraft batteries. Usually, we bombed from about 24,000 feet and had to wear oxygen masks. Our route had been planned so that the Germans would not know our target until the last few minutes.

When we reached a certain point, called the „I.P.“ (Initial Point), not far from the target, the pilot would turn the aircraft toward the target and turn over the controls to the Bombardier and the bombsight and the Bombardier would open the bomb bay doors.

The Bombardier adjusted his Norden bombsight so as to look far ahead and he continued to search, through the bombsight, until he spotted the target. Beforehand, he had entered a lot of data into the bombsight, such as altitude, type of bomb, groundspeed, etc.

When he spotted the target, he locked the bombsight’s crosshairs on it and maneuvered the aircraft with the controls of the bombsight to keep them exactly on the target as the aircraft approached.

When the aircraft got to the correct point, as determined by the bombsight from all the information the Bombardier had entered, the bombs were automatically released. The plane would give a lurch as the bombs left, the

Bombardier would call out „Bombs Away,“ and we would turn sharply and scurry for home as fast as our four little engines would take us.

During the flight, we wore a „flack vest,“ which was a vest of armor, and a steel helmet.

Our flying suits had electric wires running through them and we would plug them into a receptacle and adjust the heat as needed.

This kept us from having to wear so much heavy clothing it would impede our movements.

After takeoff, we would circle over the field until the last plane of our group took off, then form into formation and head for the coast. Enroute, we would check our guns and maybe fire a few rounds to be certain they were in working order. Each of our aircraft had ten .50 caliber machine guns firing, as I recall, 500 rounds per gun.

When the aircraft got to the correct point, as determined by the bombsight from all the information the Bombardier had entered, the bombs were automatically released. The plane would give a lurch as the bombs left, the

Bombardier would call out „Bombs Away,“ and we would turn sharply and scurry for home as fast as our four little engines would take us.

During the flight, we wore a „flack vest,“ which was a vest of armor, and a steel helmet.

Our flying suits had electric wires running through them and we would plug them into a receptacle and adjust the heat as needed.

This kept us from having to wear so much heavy clothing it would impede our movements.

The famous Norden bombsight was installed in the nose of the aircraft under the nose turret where there was a glass window for the Bombardier to look out. As the nose turret had to rotate, there wasn’t a really tight fit and I

recall that while I was hunched over the bombsight a blast of ice-cold air would hit my forehead.

Using the Norden bombsight was a job for a contortionist.

The left arm and hand had to be curled around and under the right arm, and the left hand twisted to operate one of the bombsight knobs.

After we reached our bombing altitude, usually about 24,000 feet, I had a problem with my left hand – it became so weak I could hardly use it. But of course I never told anyone or I would have been instantly grounded.

Most of the time, the target area was covered with a thick curtain of anti-aircraft fire, particularly if the target was of vital interest to the German war effort.

The Germans would put a heavy barrage over the target, knowing that we would have to fly into it.

It was very unnerving to see that hail of fire. I have seen aircraft ahead of us literally disappear as they

passed through the smoke and think to myself, „We can’t possibly go into all that!“ But we did.

It really was more frightening than dangerous. Some planes were lost, and we would get a few hits from shrapnel, but we never had any real trouble.

We learned to judge the quality of the anti-aircraft explosions; if they were just light puffs of smoke, he knew they were not so dangerous, but if the puffs were oily-looking and black, we knew they were dangerous.

We would frequently hear the sounds of small pieces of shrapnel, like hail, hitting our aircraft.

Sometimes, we ened German fighters, which we greatly dreaded, but we never had any real trouble with them over the target as they feared the anti-aircraft fire as much as we did.

When the fighters came in, I could hear all our machine guns firing, but the Navigator and Bombardier were pretty well enclosed and could only guess what was happening.

It was pretty nerve-wracking for us.

Once in a while, the bomb release mechanism would malfunction and we could not drop our bombs on the

assigned target. At these times, we had to drop them separately after the problem was corrected. On the way back home, we would look for a rail yard or bridge and would veer out of the formation long enough to drop our bombs on it.

When all our bombs fell together over a city, I remember looking down and wondering what the poor citizens were thinking with all those bombs exploding around them.

We could never hear the explosions themselves; we could see them and each of us had his own thoughts about the numerous tragedies happening on the ground but we never talked about it.

It was just a distasteful job.

After we left the coast on the return trip, we usually had no further trouble.

However, we had to be careful as, occasionally, a German aircraft would follow the group, unobserved, and catch the bombers while they were landing and were most vulnerable.

This never happened to us, but it did to some of the other groups, particularly those which were returning at night.

If there were wounded on board, the aircraft would fire red flares to alert the field ambulance.

When we landed, we were given a de-briefing at which each crew member told his version of the mission. Sometimes there would be a bottle of whiskey to pass around.

After all that, we were ready for bed.

Flying for long hours at that altitude was very exhausting.

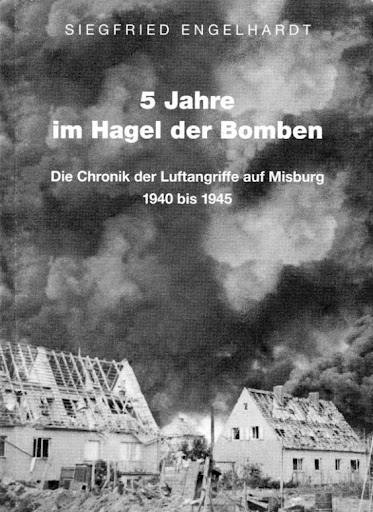

The attack on Misburg on 11/26/1944

Taken from Siegfried Engelhardt’s book „5 Years in the Hail of Bombs“ – Siegfried Engelhart, born in 1929, was from Misburg. He experienced the war years and the air raids in Misburg. He has deepened and processed his memories by interviewing contemporary witnesses. The following passages from November 26, 1944 describe the air raid from the perspective of the people of Misburg.

I myself had the opportunity to ask Mr. Engelhardt about his experiences in 2002.

That morning, 1,137 bombers and 732 escort fighters took off from England. The bombers flew into Germany in two separate streams, the northern one over Holland to the Lingen area heading for Lake Dümmer, the southern one over Belgium to the Siegen area.

The targets were railway facilities in Hamm, Altenbeken, Osnabrück, Bielefeld, Gütersloh and Herford.

But the last oil refinery still operational at the time was also in the attack program.

And that was Misburg.243 B-17 (Flying Fortress) and 57 B-24 (Liberator) bombers were planned for Misburg.

These machines flew in the northern bomber stream.At 10:46 a.m. an air raid warning was given in Misburg and shortly afterwards the town was covered in fog, apparently as a sign of bad premonition, as at this time the leading bomber units were still in the area of Lake Dümmer. They continued to fly east until they were at the height of Lake Steinhude, then the units turned to a northeasterly course and flew north past Hanover to the Soltau-Uelzen area. There, part of the units turned to a southwesterly course, the other part initially flew southeasterly towards Braunschweig, but then turned to a westerly course and flew towards Misburg via Peine-Lehrte.

This put Misburg in a pincer movement and attacked simultaneously from the northeast and east.

The first bombs fell at 12:08 p.m. and then the carpet bombing rolled over Misburg in uninterrupted succession. In total there were 14 carpet bombings with 3,300 bombs of 250 kg and 500 kg caliber. According to US information, a total of 863 tons of bombs were dropped. This amount exceeded anything that had previously fallen in an attack on Misburg.

The earthquake caused by these carpet bombings lasted half an hour. That was an endless time for the people who were huddled together in the swaying bunkers in total darkness. The roar of the detonating bombs could be heard through the ventilation shafts.

There was an oppressive silence in the bunker itself. No one said a word.

Only now and then a child cried somewhere. Everyone just hoped that the inferno would soon be over.

At the same time, however, a catastrophe struck the residents of the Teutonia residential area, who had sought shelter in a bunker on the factory premises. There were around 100 people in total, mostly women, children and elderly people. An explosive bomb hit the bunker from the side. It broke through the outer wall of one of the shelters and 45 people who had been in that room were killed. Everyone else who was in the other rooms or in the corridors escaped with a fright, but some were also seriously injured.

The survivors escaped outside and, despite the bombs still falling, first cared for the injured. Everyone was so dazed that they did not even notice what was going on around them.

There was no help from paramedics or a doctor. It was not until late afternoon that Mr. Könnecker, the head of the Misburg medical squad, arrived44 to look after the injured and – where necessary – arrange for them to be transported to hospitals.But this operation was no walk in the park for the attackers either. The German Air Force had called up another 500 fighter planes that day – including night fighters – to counter the overwhelming superiority of the attacking bomber and fighter units. Roger A. Freeman deals directly with this attack in his book „The Mighty Eight“. He reports that directly above the target (Misburg), just as the two groups of Liberator bombers were dropping their bombs, a group of Focke-Wulf fighters swooped down in several waves from above through the closely-packed bombers, bringing down 20 of them.

Four of these bombers crashed in the area between Misburger Wald and Fasanenkrug. This attack by the German fighters must have been carried out with the courage of desperation, because they not only exposed themselves to defensive fire from their own anti-aircraft guns, but when they dived after the attack they were also hit by falling bombs. This method of attack was first used by the German night fighters and was called „The Wild Boar“ in their language.

A total of 35 American bombers were shot down in this attack. The German fighter pilots themselves lost 87 aircraft. 57 pilots, including 5 squadron captains, were killed.

This description shows how relentless the air war was at this time. The high losses and the lack of fuel led to the complete collapse of the German air defense within a short time.

When the Misburg residents were able to emerge from the bunkers into the daylight after the all-clear was given at 1:24 p.m., still shocked by the events of the previous hour, they found nothing but chaos. The destruction in the town had reached a level never seen before. 500 explosive bombs had hit the DEURAG-NERAG alone. The factory was completely engulfed in flames and once again a huge cloud of smoke rose above it. The material damage was estimated at around 4.5 million Reichsmarks.

The freight railway line between the freight station and Lehrte was literally ploughed up by around 550 bombs. 50 bombs also hit the branch canal facilities. 145 bombs fell on the Misburg cement works HPC, Norddeutsche PC and Germania. The workshops of the Hermann Rethfeldt company were hit by 10 bombs.

The Teutonia, the Heag iron foundry and the Kraul & Wilkening & Stelling company were hit by around 350 bombs together. (At the time, Heag was producing grenades). All of the industrial companies hit suffered a total loss of production for an unforeseeable period of time.

40 bomb hits were counted in the area of the Hindenburg lock. The lock itself was only slightly damaged, however.

The residential areas around the streets Am Seelberg, Hannoversche Strasse, Buchholzer Strasse, Waldstrasse, Bahnhofstrasse (Anderter Strasse), Teutonia and Jerusalem were hit by a total of 800 explosive bombs. 65 houses were completely destroyed, 68 were seriously damaged, 42 were moderately damaged and 83 were slightly damaged. The damage to roofs and windows was incalculable. 1,350 citizens were left homeless.All water, electricity, gas and telephone supply lines were destroyed by 75 bomb hits and the streets were impassable for vehicles. Elementary School I at St. John’s Church was completely destroyed. The beautiful building of the Germania Pharmacy was also razed to the ground. The mayor’s office and St. John’s Church were seriously damaged and the youth center was moderately damaged.

When the Misburg residents returned to their daily routine after the initial shock and began to repair roofs, windows and doors with what had become their usual routine in order to at least make the apartments weatherproof, none of them could have guessed that just three days later a new heavy attack would take place on Misburg…